·临床研究·

【摘要】目的 研究无创检测方法踝臂指数(ankle brachial index, ABI)和外周动脉疾病(peripheral arterial disease, PAD)死亡率之间的关系。方法 自2004年7月至2005年1月在上海和北京连续入选年龄≥35岁且具有≥2项以上动脉硬化危险因素的住院患者,危险因素包括高血压,糖尿病,吸烟和高脂血症,分别测定ABI并获取基线数据,所有研究对象随访至2008年2月或研究对象死亡,平均随访(38±2)个月。结果 共入选 3732 例患者,其中PAD患病率为26%,将ABI分为≤0.4,0.41~0.90,0.91~0.99和1.00~1.40共4组,Kaplan-Meier分析显示随着ABI的降低,生存率逐渐降低(P<0.001);Cox回归分析ABI≤0.4组3年全因死亡风险和心血管疾病死亡风险分别是ABI=1.0~1.40组的3.11倍(95%CI: 1.94~4.98)和4.79倍(95%CI:2.74~8.39,ABI=0.41~0.90组是ABI=1.0~1.40组的1.53倍(95%CI: 1.20~1.96)和2.03倍(95%CI: 1.48~2.79)。结论 随着ABI的降低,PAD患者的心血管和全因死亡率呈升高趋势,ABI能预测国人PAD患者的预后。

【关键词】外周动脉疾病;踝臂指数; 死亡率

外周动脉疾病(peripheral arterial disease, PAD)是下肢动脉硬化斑块形成造成下肢缺血的一种疾病,是全身动脉硬化性疾病的表现形式之一,不同的人群其患病率不同,国外报道患病率25%左右[1-4],年龄校正的患病率为12%[5]。许多研究发现PAD与患者的心血管死亡率和全因死亡率相关。在基线研究中发现,我国PAD患病率为25.8%[6]。一项研究估计美国有超过500万的PAD患者,且容易发生心肌梗死或缺血性脑卒中等危险事件,其年死亡率约为25%[7]。经典的间歇性跛行是诊断PAD的重要依据,虽然PAD有较高的死亡风险,但是仅有少数患者有典型的间歇性跛行;研究也发现,即使没有症状的PAD患者,其死亡率也高于非PAD患者。因此,早期诊断PAD对于早期干预,指导治疗,改善预后,降低死亡率有重要意义。踝臂指数(ankle-brachial index, ABI)是下肢动脉和上肢动脉血压的比值,作为一种操作简单,无创的方法逐渐得到认可,ABI≤0.9是目前公认的PAD诊断标准,与传统的造影检查相比,其诊断特异性和敏感性均较高[8]。本研究在获得基线数据的基础上,经过随访探讨ABI和PAD患者的预后之间的关系。

1.1 研究对象

自2004年7月至2005年1月,在上海和北京地区多家医院连续入选年龄≥35岁,具有2个及2个以上动脉硬化危险因素的住院患者为研究对象。动脉硬化危险因素包括: 糖尿病,高血压,血脂紊乱和吸烟。各动脉硬化危险因素定义如下(1) 糖尿病: 有糖尿病病史,或正在接受降糖药物治疗,或症状加空腹血糖≥7mmol/L或症状加随机餐后血糖≥11.1mmol/L或口服葡萄糖耐量试验(oral glucose tolerance test, OGTT)2h血糖≥11.1mmol/L,如果无症状,需另一天证实上述指标;(2) 高血压: 有高血压病史,或正在接受降压药物治疗,或非同日重复测量收缩压≥ 140mmHg 和/或舒张压≥90mmHg(1mmHg=0.133kPa);(3) 血脂紊乱: 参照1997年发表的血脂异常防治建议[9],总胆固醇(total cholesterol, TC)>5.72mmol/L或三酰甘油(triglyceride, TG)>1.70mmol/L或高密度脂蛋白胆固醇(density lipoprotein-cholesterol, HDL-C)<0.9mmol/L或低密度脂蛋白胆固醇(low density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-C)>3.64mmol/L,至少符合其中一项定义为血脂紊乱,或正在使用降脂药物治疗的高脂血症患者;(4) 吸烟: 每天吸烟≥1支,连续吸烟1年以上。

1.2 排除标准

(1) 不符合入选标准;(2) 恶病质;(3) 严重呼吸功能不全; (4) 严重肾功能不全;(5) 严重肝功能不全;(6) 严重心功能不全;(7) 严重心律失常,如频发早搏、房颤,影响四肢血压测量或者严重影响ABI结果。

1.3 踝臂指数的测量方法和标准

采用5MHz超声探头(仪器型号Elite Model 100R)测定,ABI值为胫后动脉或足背动脉收缩压与前臂收缩压的最高值之比[6]。删除ABI>1.40的数据,考虑可能造成假阴性。

1.4 外周动脉疾病的诊断标准

根据美国ACC/AHA外周动脉疾病诊断和治疗指南[10],将ABI≤0.9定义为外周动脉疾病。

1.5 随访

共入选3732例患者,其中969例为PAD,自2007年12月至2008年2月对研究对象进行随访,随访终点为研究对象死亡或随访结束,主要终点事件为死亡。

1.6 统计学处理

连续性变量采用![]() ±s,分类变量采用百分数,按ABI≤0.4,0.41~0.90,0.91~0.99和1.00~1.40分4组,4组之间的连续性变量的比较采用ANOVA检验,在ABI 4组中分类变量的比较采用卡方检验。采用单因素Kaplan-Meier分析ABI 4组中3年生存情况;采用Cox回归校正糖尿病,高血压,吸烟,高脂血症,慢性肾病史,年龄,性别等相关因素后研究与ABI=1.0~1.40相比,ABI≤0.4、ABI=0.41~0.90和ABI=0.91~0.99组与3年累积全因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率的之间的独立关系。所有资料采用SPSS 13.0版本计算。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

±s,分类变量采用百分数,按ABI≤0.4,0.41~0.90,0.91~0.99和1.00~1.40分4组,4组之间的连续性变量的比较采用ANOVA检验,在ABI 4组中分类变量的比较采用卡方检验。采用单因素Kaplan-Meier分析ABI 4组中3年生存情况;采用Cox回归校正糖尿病,高血压,吸烟,高脂血症,慢性肾病史,年龄,性别等相关因素后研究与ABI=1.0~1.40相比,ABI≤0.4、ABI=0.41~0.90和ABI=0.91~0.99组与3年累积全因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率的之间的独立关系。所有资料采用SPSS 13.0版本计算。P<0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2.1 总体结果

共入选3732例研究对象,其中PAD患者969例(占26%),平均随访(38±2)个月,共失访的522,失访率13.9%,其中PAD患者失访150例。

2.2 失访对总体结果的影响

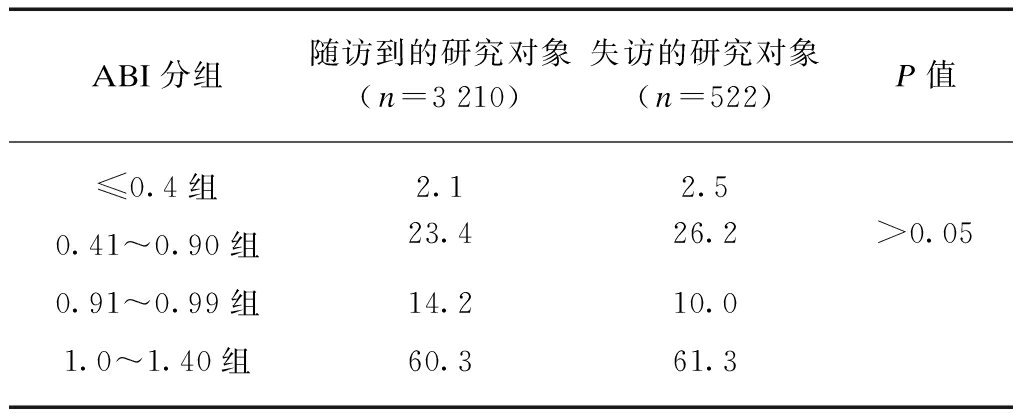

对4组中随访到和失访的研究对象进行检验,经检验,随访到的研究对象和失访的研究对象基线在4组中的比例差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),说明使用3210例随访到的研究对象进行统计,相当于从 3732 例研究对象中抽取3210例来代表总体水平。失访对总体结果的影响差异无统计学意义,见表1。

2.3 基线情况

表2显示4组的基线情况随ABI的降低年龄逐渐升高(P<0.001),4组中性别、收缩压、脑卒中病史、冠心病史、心肌梗死病史之间差异有统计学意义(P均<0.001);动脉硬化危险因素方面,合并糖尿病、高血压和吸烟的比例随ABI值的降低逐渐升高(P均<0.05)。

表1 随访和失访的研究对象在ABI 4组中的比较

Tab. 1 Number of participants in four ABI groups (%)

ABI分组随访到的研究对象(n=3210)失访的研究对象(n=522)P值≤0.4组2.12.50.41~0.90组23.426.2>0.050.91~0.99组14.210.01.0~1.40组60.361.3

表2 4组研究对象的基线情况

Tab.2 Baseline characteristics among four ABI groups

项 目ABI分组≤0.4组(n=69)0.41~0.90组(n=750)0.91~0.99组(n=455)1.0~1.40组(n=1936)P值 一般情况 年龄/岁75±772±1068±1165±11<0.001 性别0.001 男性/%44.950.747.556.0 女性/%55.149.352.544.0 血压/mmHg 收缩压145±25143±24142±24138±23<0.001 舒张压80±1281±1381±1381±13>0.05 既往病史 冠心病/%62.361.757.652.7<0.001 心绞痛/%56.557.755.249.9<0.01 心肌梗死/%33.321.214.313.2<0.001

(续表2)

项 目ABI分组≤0.4(n=69)0.41~0.90(n=750)0.91~0.99(n=455)1.0~1.40(n=1936)P值 PTCA/%8.711.212.311.8>0.05 CABG/%1.43.53.72.4>0.05 脑卒中/%63.852.141.537.7<0.001 慢性肾病/%9.013.110.29.4>0.05危险因素 糖尿病/%56.546.938.234.4<0.001 高血压/%84.179.772.370.7<0.001 吸烟/%49.342.536.038.5<0.05 血脂紊乱/%44.445.542.040.6>0.05生化检查 TC/(mmol·L-1)4.68±1.154.66±1.184.79±1.174.60±1.12>0.05 TG/(mmol·L-1)1.78±1.981.71±1.331.66±1.141.63±1.09>0.05 HDL-C/(mmol·L-1)1.16±0.291.18±0.411.24±0.431.22±0.42<0.05 LDL-C/(mmol·L-1)2.78±0.842.75±0.892.73±0.852.73±0.85>0.05 血糖/(mmol·L-1)6.68±2.486.69±3.066.56±3.136.36±2.76>0.05 CRE/(μmol·L-1)100.5±32.4107.9±80.291.89±58.298.96±101.7<0.05 UA/(mmol·L-1)339±131345±131313±115329.9±115<0.001ABI0.21±0.160.73±0.140.95±0.031.12±0.09<0.001

2.4 3年随访

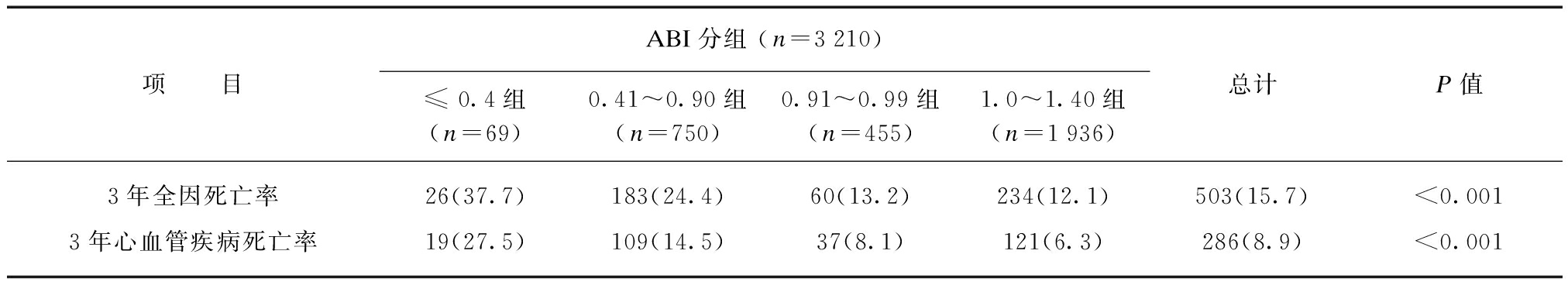

在3年随访结果中发现,无论3年累积全因死亡率还是3年累积心血管疾病死亡率,都随着ABI值的降低,其死亡率逐渐升高,差异有统计学意义(P均<0.001),见表3。

表3 4组中3年累积全因死亡率和3年累积心血管疾病死亡率的比较

Tab.3 All cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in four ABI groups [n](%)]

项 目ABI分组(n=3210)≤0.4组(n=69)0.41~0.90组(n=750)0.91~0.99组(n=455)1.0~1.40组(n=1936)总计P值3年全因死亡率26(37.7)183(24.4)60(13.2)234(12.1)503(15.7)<0.0013年心血管疾病死亡率19(27.5)109(14.5)37(8.1)121(6.3)286(8.9)<0.001

2.5 单因素Kaplan-Meier分析

4组生存概率均随着ABI值的降低而逐渐降低,在ABI<0.9的研究对象中,ABI≤0.4的研究对象生存概率明显低于ABI为0.41~0.9的研究对象(约10%),所有差异有统计学意义(P均<0.001),见图1、2。

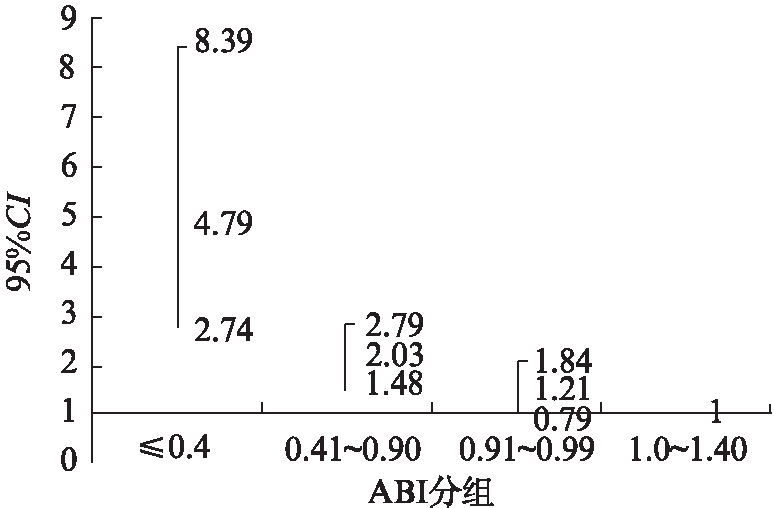

2.6 Cox回归分析

校正糖尿病、高血压、吸烟、高脂血症、慢性肾病史、年龄、性别、冠心病和脑卒中病史等因素后,与ABI=1.0~1.40相比,ABI≤0.4、ABI=0.41~0.90和ABI=0.91~0.99组和3年累积全因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率的独立关系,见图3、4。

图1 4组的全因死亡率

Fig.1 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all cause mortality among four ABI groups

图2 4组的心血管疾病死亡率

Fig.2 Kaplan-Meier survival curves for cardiovascular mortality among four ABI groups

图3 ABI与三年全因死亡率的独立关系

Tab.3 Tab Independence relationship between ABI and cause mortality

图4 ABI与三年全因死亡率的独立关系

Tab.4 The independence relationship between ABI and all cause mortality

动脉粥样硬化性疾病是是我国乃至世界最常见的死亡原因,尤其是心血管疾病,该病致死致残性极高,如心肌梗死、脑卒中等已成为全世界的负担,占用了大量的医疗资源[11]。早期检测动脉硬化成为近期研究的热点,然而简单、无创、易操作性的检测方法成为临床筛选动脉硬化性疾病的颇具前途的工具,如颈动脉中层斑块厚度(IMT),钙化积分,踝臂指数(ABI),脉搏波传导速度(PWV)等。国外的临床流行病学研究认为低ABI增加了心血管疾病的死亡风险[12-15],ABI被广泛用来预测心血管疾病的死亡风险,然而我国并没有该方面的系统的研究资料。

该研究是我国首次进行的关于PAD和ABI的随访研究,PAD在具有多重动脉硬化危险因素的住院患者中的基线患病率为26%,在基线调查时可见ABI越低,合并冠心病、脑卒中等病史比例越高,合并糖尿病、高血压和吸烟的比例越高,根据既往的研究结果,ABI越低动脉硬化风险越高,该研究基本与以往的研究结果相似。和ABI=1.0~1.4相比,ABI≤0.4者,更容易合并各种心血管疾病危险因素,如高血压、糖尿病、脑卒中等,ARIC研究也有同样的报道[16-17]。

随访结果发现ABI≤0.4组的死亡率最高,全因死亡率高达38%,心血管疾病死亡率为27.5%,无论全因死亡率还是心血管疾病死亡率,均随着ABI的升高死亡率逐渐降低。这点与McKenna等[18]的研究相似,他们发现ABI=0.4的研究对象中,5年随访死亡率高达50%,ABI=0.7的人群也高达30%,尽管本研究随访时间约为3年,但初步来看,我国PAD人群的死亡率很接近于Mckenna的5年随访结果,因此粗略估计我国PAD患者5年死亡率将高于Mckenna报道的结果。

采用生存曲线观察ABI 4组和3年死亡率的关系,发现ABI=0.91~0.99和ABI=1.0~1.40两组无论在全因死亡还是心血管疾病死亡,其生存概率比较相似,而且显著高于ABI<0.9组的研究对象,虽然ABI≤0.4和ABI=0.41~0.9两组中ABI均小于0.9,但是从单因素分析上看,ABI≤0.4的研究对象生存概率明显低于ABI为0.41~0.9的研究对象,总体趋势是研究对象的ABI越低,其生存概率越低。Sikkink等[19]的研究在进行5年的随访时,ABI<0.5的患者有63%的研究对象生存,ABI=0.5~0.69的人群为71%,ABI=0.70~0.89者为91%。该研究和本研究结果相似: 即ABI值越低生存率越低。

采用Cox回归校正相关因素后,发现3年累积全因死亡风险: 与ABI=1.0~1.40组相比较,ABI≤0.4组3年发生死亡风险高达3.105倍,ABI=0.41~0.90组死亡风险高达1.534倍;3年累积心血管疾病死亡风险: ABI≤0.4组3年发生心血管疾病死亡风险是ABI=1.0~1.40组的4.794倍,ABI=0.41~0.90组死亡风险为2.031倍,说明ABI越低,相对于正常人群来说死亡风险越高。一项关于ABI的metaanalysis显示,将ABI分为10个层次,和ABI=1.11~1.20相比,ABI低于1.11时,无论性别,随着ABI的降低死亡风险逐渐升高[20]。

著名的HOPE试验亚组分析[21],对关于3099例PAD患者长达4.5年的随访,非PAD患者4.5年全因死亡率为8.5%,心血管疾病死亡或心肌梗死或脑卒中的复合终点事件发生率高达13.1%,在PAD患者中ABI<0.6的患者全因死亡率明显高于ABI=0.6~0.9的患者(14.2%vs12.4%),心血管疾病死亡或心肌梗死或脑卒中的复合终点事件发生率分别为18.0%和18.2%,均显著高于非PAD患者的13.1%(P<0.0001)。

无论是McKenna和Sikkink的研究,还是Ostergren J[21]的研究,和我们的研究结果相似,均证实随着ABI水平的降低,全因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率都逐渐升高,因为动脉硬化是一种全身系统性疾病,全身血管都存在动脉硬化的发生,PAD和冠心病,脑卒中等具有相同的危险因素,ABI检测下肢动脉硬化的同时提示全身动脉硬化性疾病的发生,若由于下肢动脉硬化导致低ABI,估计全身血管均发生了动脉硬化性疾病,所以,一些冠心病、脑卒中等疾病的发生可能使得全因死亡率和心血管疾病死亡率升高,促进动脉硬化的蛋白质C也能同时加重PAD的进展[22];同时也从一个侧面反映ABI作为一种无创、简单易操作的工具可用来早期检测动脉硬化,尤其对于没有间歇性跛行的PAD患者,能早期诊断疾病,进行疾病的危险分层,判断预后,均起到了重要的作用,而且此检测简单,易于推广,具有广泛的应用前景。

【参考文献】

[1] Meijer WT, Hoes AW, Rutgers D, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: The Rotterdam Study[J]. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 1998,18: 185-192.

[2] Newman AB, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Rutan GH, et al. Lower extremity arterial disease in elderly subjects with systolic hypertension[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 1991,44: 15-20.

[3] Grenon SM, Vittinghoff E, Owens CD, et al. Peripheral artery disease and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease: insights from the Heart and Soul Study[J]. Vasc Med, 2013,18(4): 176-184.

[4] Zheng ZJ, Sharrett AR, Chambless LE, et al. Associations of ankle-brachial index with clinical coronary heart disease, stroke and preclinical carotid and popliteal atherosclerosis: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study[J]. Atherosclerosis, 1997,131: 115-125.

[5] Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Langer RD, et al. The epidemiology of peripheral arterial disease: importance of identifying the population at risk[J]. Vasc Med, 1997,2: 221-226.

[6] Hasimu B, Li J, Nakayama T, et al. Ankle brachial index as a marker of atherosclerosis in Chinese patients with high cardiovascular risk[J]. Hypertens Res, 2006,29: 23-28.

[7] Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S. The fate of patients with critical leg ischemia[J]. Semin Vasc Surg, 1999,12: 142-147.

[8] Jeevanantham V, Chehab B, Austria E, et al. Comparison of accuracy of two different methods to determine ankle-brachial index to predict peripheral arterial disease severity confirmed by angiography[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2014,114(7): 1105-1110.

[9] 方圻,王钟林,宁田海,等.血脂异常防治建议[J].中华心血管病杂志,1997,03: 10-11.

[10] Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, et al. ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease; American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; Vascular Disease Foundation. ACC/AHA 2005 Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): a collaborative report from the American Association form Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Peripheral Arterial Disease): endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; TransAtlantic Inter-Society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation[J]. Circulation, 2006,113: e463-654.

[11] Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, et al. Comparison of global estimates of prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: a systematic review and analysis [J]. Lancet, 2013,382(9901): 1329-1340.

[12] Papamichale CM, Lekakis JP, Stamatelopoulos KS, et al. Ankle-brachial index as a predictor of the extent of coronary atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease [J]. Am J Cardiol, 2000,86: 615-618.

[13] Abbott RD, Petrovitch H, Rodriguez BL, et al. Ankle/brachial blood pressure in men>70 years of age and the risk of coronary heart disesase[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2000,86: 280-284.

[14] Resnick HE, Lindsay RS, McDermott MM, et al. Relationship of high and low ankle brachialindex to all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality: the Strong Heart Study [J]. Circulation, 2004,109: 733-739.

[15] Van der Meer IM, Bots ML, Hofman A, et al. Predictive value of noninvasive measures of atherosclerosis for incident myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study[J]. Circulation, 2004,109: 1089-1094.

[16] Weatherley BD, Nelson JJ, Heiss G, et al. The association of the ankle-brachial index with incident coronary heart disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study, 1987-2001[J]. BMC Cardiovasc Disord, 2007,7: 3.

[17] Violi F, Daví G, Hiatt W, et al. Prevalence of peripheral artery disease by abnormal ankle-brachial index in atrial fibrillation: implications for risk and therapy[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2013,62(23): 2255-2256.

[18] McKenna M, Wolfson S, Kuller L. The ratio of ankle and arm arterial pressure as an independent predictor of mortality[J]. Atherosclerosis, 1991,87: 119-128.

[19] Sikkink CJ, van Asten WN, van’t Hof MA, et al. Decreased ankle/brachial indices in relationto morbidity and mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease [J]. Vasc Med, 1997,2: 169-173.

[20] Ankle Brachial Index Collaboration. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis [J]. JAMA, 2008,300: 197-208.

[21] Ostergren J, Sleight P, Dagenais G, et al. HOPE study investigators. Impact of ramipril in patients with evidence of clinical or subclinical peripheral arterial disease [J]. Eur Heart J, 2004,25(1): 17-24.

[22] Komai H, Shindo S, Sato M, et al. Reduced protein c activity might be associated with progression of peripheral arterial disease [J]. Angiology, 2014, 12, pii: 0003319714544946. [Epub ahead of print].

Association between ankle brachial index and mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease

【Abstract】Objective To investigate the association between ankle brachial index (ABI) and mortality of patients with peripheral arterial disease (PAD). Methods Patients aged over 35 years with at least two atherosclerotic risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes and smoking) were consecutively enrolled from the hospitals in Shanghai and Beijing between July 2004 and Jane 2005. ABI was measured and questionnaire survey was conducted for the baseline characteristics of patients. The participants were followed up till February 2008 or deceased. Results A total of 3732 inpatients were enrolled, including 969 cases of PAD with a prevalence rate of 26.0%. Total 3210 eligible patients were divided into 4 groups according to ABI value: ≤0.4 group (n=69), 0.41-0.90 group (n=750), 0.91-0.99 group (n=455) and 1.00-1.40 group (n=1936). Kaplan-Meier analysis showed the survival was aggravated as ABI decreased; Cox regression analysis showed that using 1.0-1.40 group as reference, the risks of all-cause mortality and of cardiovascular mortality in ABI≤0.4 group were 3.11 times (95%CI: 1.94-4.98) and 4.79 times (95%CI: 2.74-8.39), respectively; those of 0.41-0.90 group were 1.53 times (95%CI: 1.20-1.96) and 2.03 times (95%CI: 1.48-2.79), respectively. Conclusion Ankle brachial index is an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with peripheral arterial disease.

【Key words】peripheral arterial disease; ankle brachial index; mortality

doi:10.16118/j.1008-0392.2015.02.017

收稿日期:2014-09-15

【中图分类号】R 54

【文献标志码】A

【文章编号】1008-0392(2015)02-0074-07